Even today, the sea does not want to listen to reason. The Tiran Channel’s rolling, mighty waves crash strongly onto the outcropping sections of the great wreck, while our little dinghy and we float like corks toward its rusty, sharp and ghostly remains.

We were waiting since days, weeks, for the right moment to dive on the Million Hope, but since it did not come, we chose a bad one whatever. Under these conditions, it would have been too difficult and dangerous to reach the site by sea starting from the Sheikh Coast; therefore, Pierpaolo opted for an approach by land, relying then on the assistance and the dinghy of a local diving center for the actual dive.

Now, surrounded by the cobalt blue of the waves, by their incessant splashing and the swinging turquoise of a cloudless sky with no horizon, we hear rising from the sea that same force which, perhaps, pushed the steel ship to crash onto the reef. It seems vibrating also through the floats’ canvas, like the breath of an immense and omnipotent creature. Or maybe it was really and only the smoke of the fire, burst aboard a few hours before, to cause the route’s loss to the Million Hope helmsman, but the Channel allows no mistakes, and that was enough for it to go banging its 25,000 tons of tonnage onto corals.

The crew was immediately rescued while the cargo, consisting of phosphates and potassium, was recovered more calmly later. The ship had sailed the day before from the port of Aqaba, in Jordan, and was bound for Taiwan when, on the morning of 20 June 1996, it stopped in Egypt forever, against the Nabq coral reef.

The Million Hope was a cargo ship 175 meters long and 25 meters wide; it was equipped with four large central holds and a fifth, smaller one, at the bow.

Four independent cranes, aligned centrally along the major axis of the hull, served all holds. Perpendicular to the axis, instead, there were the colossal pedestals above which the arms were operated, placed transversely over the bulkheads between the major holds. This configuration made it completely independent in the loading and unloading maneuvers, at any port.

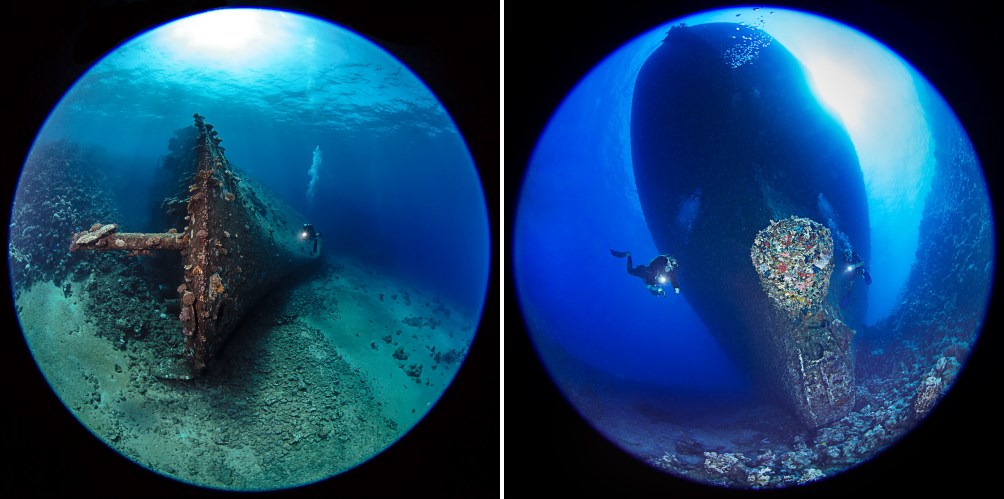

Launched in Japan in 1972 under the name of Ryusei Maru, it changed hands for the last time in the same year when it stopped staying afloat, right here, in Nabq, becoming first Cypriot for a few months and then “Egyptian” forever. Today, it lies on this 25-meter seabed with the starboard side almost resting on the reef. The hull, aft, would seem almost entirely intact, if only it wasn’t amputated of the rudder and of the large bronze propeller.

Then, beyond the half-ship, it breaks and reclines towards the opposite side, until it bumps into its own bow bent at ninety degrees and poured with the keel to the sea. There is no way or time to mention any briefing: we hardly can set us up for the dive.

This wave is twitching us like beasts of burden and those who must prepare their cameras or REB, like Rino and Pierpaolo, is entitled to swear. However, the cursing cease immediately after entering the water: Below is fantastic!

The visibility is amazing and the show is one of those that strucks you dumb. Yes, I know you do not talk under water, but it is different when also your mind hushes-up…

Despite the size of the wreck, perhaps the largest of the entire Red Sea, we can enjoy an almost total overlook.

The eye runs a bit everywhere, without knowing well where to rest, because here, really, there is no shortage of cues. In addition to the sunken ship, there are schools of fish such as to steal the scene. Among many other things scattered on the seabed, it strikes immediately a large metal structure, asleep a few tens of meters from the stern of the wreck.

This is a crawler crane, armed with a huge pylon, facing the sky.

Soft corals and benthic life encrust it so much that its shapes are barely recognizable. The most colorful and non-migratory fishes, typical of these waters, elected it as their dwelling and surround it densely, in a large cone, so that the lights of my buddies make it look an enlightened Christmas tree. Alone, this tracked vehicle could be the subject of an entire dive.

However, it was not part of the Million Hope equipment, but it fell into the water falling from a barge set up during the recovery operations, perhaps of the propeller, the rudder or whatever. They left it here at the bottom, like everything that hadn’t enough value to be recovered.

However, the hull of the big cargo beast is very long to cover completely, and we cannot tarry too much on something so marginal and alien to the wreck. Even when the first fractures appear, in the starboard side, which seem to inviting us to enter the belly of the ship… Pierpaolo makes me sign that it is better to continue.

In the scouting of the external part, we are equally caught by surprise by what we bumped into at the bow: the entire fore is twisted, almost torn from the rest of the ship body and the huge base of the last crane seems to be a curtain for the show that is about to open up in front of us. Just around the corner, in the full light of the sea, a large school of rainbow-colored Platax appears looming, sliding in front of our mask’s glass.

A meter before, you could not see one. What’s more, the school of batfish is scattered by the arrival of a fast “swarm” of huge unicorns, which rush against the tilted deck in hundreds, like a wall. They look like a greenish flooding river from the unceasing flow, banging on the steel of this deck, suddenly diverting its course.

A little further up I see some jackfish coming, silvery and shimmering, almost as if some invisible and mysterious bait lured all the fishes of the sea here.

Turning to look at them, I also see a squadron of long barracudas, frowning and severe, which I discover immediately being a part of a more extensive and numerous conical formation, not far away. In a matter of seconds I realize I have seen more fishes here than in a dive at Ras Mohammed. I did not expect it.

Nevertheless, not even in this whirlwind of spectacular life we can linger more than we should, since the phase of the wreck’s penetration awaits us, from the stern castle, which already appears subject to an important undertow. Backwards, we retrace the entire length of the great hull, this time above the deck, flying and swaying, from starboard to port, up to the quarterdeck.

The undertow here, a few meters deep, is definitely the dominant force: the one to keep at bay. To enter from the ports, the hatches and through the internal passages we must take aim, synchronize with the waves’ motion and, where necessary, help us with our hands if we do not want to crash.

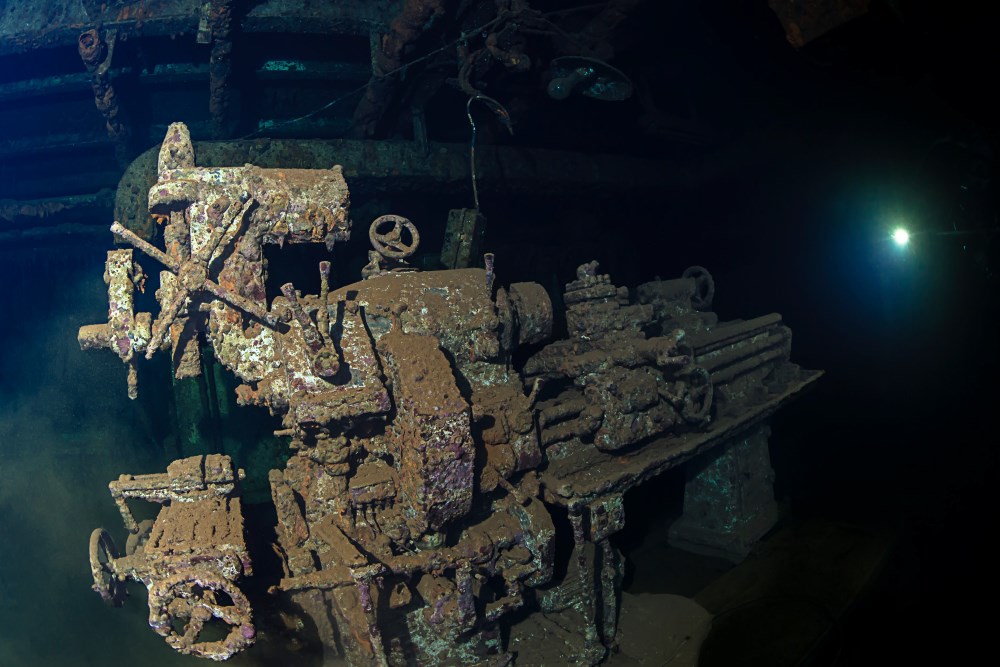

In a chasm opening at the prow of the quarterdeck, among a myriad of scrap and other structures, the rocker arms’ valves of one of the engines are easily distinguishable. It seems that the Million Hope had two engines, both connected to a single tree and a single propeller, although the position of this head seems very central to imagine another diametrically opposite.

Maybe there were two aligned engines, either it’s my perception of position to betray my sense of direction, darkened by the never-ending rocking we are hostages hereof.

We get in from a large lateral fracture in the midst of this turmoil of twisted steel, and begin to search the maze of interiors as if it was an alien building fallen on earth, indeed, in the sea. Pierpaolo leads us through the narrow rooms and corridors that tangle in the belly of the ship, swinging up and down like a drunk who struggles to maintain a decent posture. We mimic him.

His figure is illuminated, at times, both by the reflection of the strobes of his camera and by the continuous light beams coming from Rino’s headlights that, pray to the undertow’s grip, glimmer here and there like strange explosions in the dark.

Attached to the ceiling I see layers of material with a well-defined, regular thickness, resembling polystyrene sheets stacked and pressed at the top by the hydrostatic thrust. However, to the touch I find them slightly more fibrous and compact than any polymer I have ever touched. I just cannot explain what they are.

We proceed. Pierpaolo approaches a trapdoor on the floor, enlightening it through his camera’s focus light. We can glimpse immediately a descending handrail showing the presence of a service ladder, whose state of preservation we cannot care less since we will not have to step on it.

The passage is narrow and not devoid of roughness, even for those moving on three dimensions and in the absence of gravity like we are now, and the same applies to the environment to which the ladder leads.

A large reservoir, almost intact, occupies almost entirely the space in the very low hold. Pierpaolo tries to spell-out the name among the bubbles, moving his regulator: DE-A-I-NA-TO. Encrusted pressure gauges and valves on a plant the size of a few inches suggest that he must have pronounced the word “desalinator”.

Below, the undertow is almost imperceptible, but another wave, just as aggressive, keeps our alert level high. It is a sound wave. It is a loud, bleak noise, a rhythmic, dull thud pervading all the water around, making rattling not only our eardrums’ membranes, but also the whole body and its senses.

It seems like a big heavy metal sheet at the undertow’s mercy, slamming to the wave’s rhythm against who knows what. Who knows where.

As is well known to divers, the sound waves traveling in the water propagate much faster than in the air, preventing the human brain to determine the direction and the origin of the sound, and therefore the source of the perceived noise and its real intensity or, at least, the one it would have if we hear it in the air. This noise is not the most comforting, especially when perceived being buried in the narrow belly of a wreck in an advanced state of deterioration.

The mind runs by itself to browsing through the images seen little before, of pipes and structures detached from the bulkheads and ceilings, heavily fallen on the bridges and on floors… I’ll leave the rest to your imagination.

The exploration of the Million Hope is an exciting experience for any diver, even the most experienced, but it is advisable performing it in two separate dives, and under weather and sea conditions absolutely optimal. While we leave the tangle of metal sheets, following the natural light blades slipping between the hatches and larger cracks, I notice that my computer already marks 99 minutes of dive time.

I have no decompression, since we spent the last half hour between 15 and 6 meters deep and I just need to ascend gently along the safety sausage’s line I’m launching, before I can regain the dinghy-boat amidst the waves and … before we can tell our 100 minutes on the Million Hope wreck.

WORDS and PICTURES by Davide Boschi, Rino Sgororbani, Pierpaolo Peluso