The Amphiprion bicintus clown fishes are part of the Amphiprioninae subfamily and get their name from the funny, brisk movements and the vibrant coloration.

The body is high, the head is small, and the dorsal and ventral profiles are very convex. The pectoral fins are very large, trapezoidal but rounded. Thicker rays support the first half of the dorsal fin while the second part is softer. The anal fin is short and elongated. The ventral fins, rhomboid, are very pointy. The caudal fin has deltoid shape, with rounded corners. The adult specimens’ pattern contemplates a vivid orange-yellow background, with a soft-edged reddish-brown patch that starts from the head up to 3/4 of the body. From the back, originate two irregular white-blueish vertical bands, bordered in black, the first of which forms on the forehead, when viewed frontally, a characteristic inverted V.

This species is widespread in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Inhabits atoll lagoons and coral reefs. In the taxonomic classification, they fall into the great family of Pomacentridae, which have a gill operculum equipped with a spine. There are 28 known species of these fish, 27 of which belong to the Amphiprion subfamily and only one to the Premnas subfamily. The Amphiprion ocellaris, one of 27 species, has become by now a myth for young people, thanks to the famous movie Finding Nemo that sees it as the main protagonist. However, its color is bright orange and lives in the eastern Pacific and in northern Australia.

Moreover, in the area surrounding New Guinea lives his doppelganger: the Amphiprion percula. The distribution areas of the two species do not overlap even partially and it is therefore appropriate to identify them properly. These fish, with diurnal habits, live in mutual symbiosis with the anemones of the genus Heteractis, with which remain in close contact and both populations benefit from this association.

The clown fish, to protect themselves from predators, manages to squirm nimbly among the stinging tentacles of the anemones. The exact mechanism that allows the fish its immunity to the anemone’s venomous nematocysts is, even today, a subject of debate. The first theory assumes that the clownfish is able to absorb on its skin the mucus produced by the anemone, made up of glucose, which prevent the stinging cells of the commensal to recognize it as food. According to another theory, the fish’s mucus imitates the anemone’s outer surface, which is why the clown fish takes, in fact, several days before adapting to a new species of Heteractis with which it comes into contact. It is also possible, lastly, that the dermis of the clown fish lacks of certain biochemical substances that activate the stinging discharge from the capsules, as it happens instead for the other fishes. To return the favor, the guest protects his anemone from predators, such as butterfly fish and trigger fish, and cleans it from parasites. To the detriment of the popular beliefs, they are territorial fishes and are able to deliver small bites and attacks even to divers, when approaching excessively to their “home”.

They are hermaphrodite, feed on zooplankton and anemone’s leftovers, live only about ten years and are distributed in the Red Sea, Indian Ocean and Western Pacific. Many species live in small groups on one or more contiguous anemones, respecting a strict social hierarchical organization: newborn clownfish are all males, and leader of the group is the only big dominant female, the matriarch. Her male companion is the only sexually mature, while other individuals yet are not. Thus, only the female and the mature male can procreate, while every other smaller male clownfish, whose growth is repressed by social oppression, occupy the lower ranks in the family hierarchy. Upon the female’s death, the dominant male changes sex and matures within a week, taking on her place, while all the rest of immature males moves one place forward in the hierarchy. Before the female deposes the eggs, the male is responsible for the cleaning of the substrate to the anemone’s foot, where the eggs will be laid. At this point, the female reaches the male for starting the reproduction and lays the eggs the male fertilizes. Then the male will again be responsible for their cleaning and must flutter its pectoral fins to keep the surrounding water moving. In return, the anemone will protect the eggs laid on the substrate (about 250) with its tentacles. During development, the eggs change color and, from the early days, is possible to glimpse the eyeballs of the larvae peeping out from the eggshell. The hatching takes place within a week or so, when there is not excessive enlightenment and juveniles, after a short period of pelagic swimming, quickly become assiduous visitors of seabed and anemones.

These are fish reaching a dimension no larger than 10 cm in length and there is a sexual dimorphism between the female, which is larger, and the male tending instead to have smaller dimensions. In the area surrounding New Guinea lives his doppelganger: the Amphiprion percula. The distribution areas of the two species do not overlap even partially and it is therefore appropriate to identify them properly.

Unfortunately, popularity of the film “Finding Nemo” meant an exponential growth of the purchase of clown fish in aquariums and pet stores, with very serious consequences for both species. It is therefore of concern to experts of avoiding to more and the less young the breeding of these small fish. In fact, the clownfish is suitable only to the care of expert salt-water aquarists, although I personally do not believe it is right in many respects. As we know, everyone acts according to his conscience, but many clown fish die during the journey that leads them to local pet stores. In the aquariums, in addition to being difficult to acclimatize, they suffer from parasitic diseases of the skin, living consequently a shorter and certainly sadder life than in the wild.

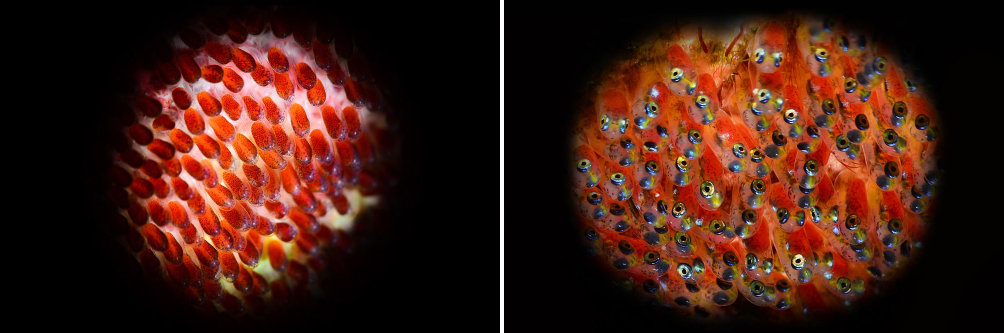

Stage #1 on the left and Stage #2 on the right

Stage #1

In the first stage, the female laid the eggs since 2-3 days. They appear distant from each other and, inside, the embryo is still not formed.

Stage #2

After 10 days from phase 1, we can notice how much the eggs increased their dimension and are consequently more closely spaced. Inside it is possible to notice a well-formed embryo, complete with large colored eyes. In 2-3 days, the eggs will hatch and will give life to many small black fishes.

WORDS by Francesca Romana Reinero and PICTURES by Alessandro Giannaccini